More interesting stuff about feeding.

feeding protien patties

Anybody who raises livestock knows that success depends on making sure that the animals are properly fed at all times. Sometimes feeding is as simple as turning the animals out to pasture, but at other times, particularly in winter, feed must be supplied. Depending on the quality of that feed, nutritional supplements may be necessary as well. Even when livestock might be able to survive on their own, good managers provide supplements, since there is no profit in animals that are just getting by.

Contrary to what many beekeepers think, the same reasoning applies to bees. Some years and some places, bees may be able to take care of themselves, but when kept in large yards, especially in areas where monoculture has become the norm, and when the hives are intensively managed, there is a real possibility that bees may run short of good pollen or honey stores at several times of the year. Weaker hives may be unable to compete, and are particularly at risk.

Chances are, most hives will survive, but they may fail to thrive. If there is a shortage of either pollen or honey, hives will reduce or stop brood rearing, and even tear out half-grown brood. Any larvae that are raised at such times will be malnourished and, when they become adults, will not be as good nurses and foragers as they might have been. The effects of even temporary starvation can last for generations, and will have continuing negative impacts on splitting, honey crops, and on wintering success.

Most beekeepers can detect when their hives are short of honey, but far fewer can determine with certainty when their bees are short of protein. As the amount of uncultivated, wild area in agricultural regions has diminished in recent years, and intensive farming has reduced the variety of natural forage, more and more progressive beekeepers are routinely feeding protein supplement in spring and fall. They know that, even if pollen appears to be abundant in a hive, that the pollen may all come from one floral source -- possibly one that is inferior -- and prove to be an incomplete diet for the bees.

Careful attention to nutrition has become even more important in recent years because adults and brood now are often parasitized by mites. Supplementary protein, fed as patties, helps balance the diet and ensures adequate nutrition, both for the adult bees and for the brood being fed.

Carbohydrate shortages are easily made up with honey or with sugar syrup and most beekeepers know how to feed syrup or honey successfully, but far fewer understand protein supplementation. Protein is usually fed as a patty on the top bars of the brood chamber that contains the open brood. Careful positioning of the patty is very important. Unless the patty is within a few inches of open brood, the patty will often not be consumed, and the beekeeper may blame the patty. Often, if there are only small patches of brood on a frame or two, only the portion of the patty directly over that brood will be consumed, and the corners further away will be left untouched by the bees until the brood area expands.

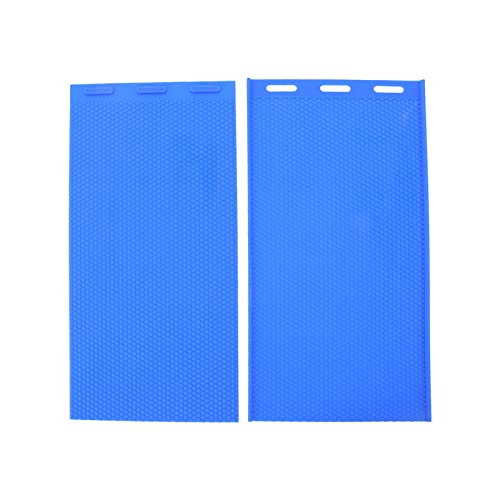

Protein supplement patties are usually made of relatively cheap high protein food ingredients like brewers yeast and soy flour (both must be suitable for bees ? see a bee supply specialist), plus trapped pollen and sugar. Although pollen is a valuable ingredient, it is expensive and is not always available. Moreover, unless the pollen is sterilized by radiation, patties with pollen will spread chalkbrood and possibly foulbrood, and as a result many beekeepers prefer to use patties that contain no pollen.

Pollen and sugar both make patties attractive to the bees. Patties with a high proportion of trapped pollen will be consumed about three times more quickly than those without any pollen content, however, if sugar is used to make up about 50% of the dry ingredients in patties, those patties will be eaten at an acceptable rate, and even consumed at times of the year when natural pollen is being brought in by foragers.

Pollen is particularly useful if patties with low sugar content are being fed, since bees really don't care much for yeast or soy patties unless the patties contain lots of sugar. However, if you use enough sugar, the bees will eat anything you put with it, and you don't really need pollen. We generally use at least 50% sugar (calculated on the dry part of mix) and find that bees will eat patties -- even with zero pollen content -- at any time of year, regardless of whether there is natural pollen available in the fields or not.

Although bees will benefit from protein feeding at any time of year when they are confined, other than winter, spring is the traditional time to feed patties. Stimulating brood rearing is often the stated goal, but causing early brood rearing by using substitutes and supplements can be tricky. Once the bees are induced to raise unnatural amounts of brood by feeding, they must be supplied with the diet continuously and never allowed to run out until natural pollen comes in reliably. If they run out -- even for a day -- the brood they have started may be thrown out or develop poorly. Brood rearing takes a lot out of the old wintered bees, and if the first spring brood cycle does not successfully raise new nurse bees, their fat bodies may be used up and they may not be able to raise much >>

more brood later, even with fresh pollen coming in.

When feeding high-pollen patties, timing is very important. If only one very attractive patty is being fed, and fed too many days before natural pollen comes in, there is a real risk of over-stimulating too much brood rearing too early. If additional patties are not put on the hives before the previous patties are completely consumed, and if natural or stored pollen does not become available, as previously mentioned, the bees may actually tear out some of the brood that has been initiated as a result of the feeding! Feeding too early, with too attractive and short-lived a patty, and failing to keep the bees supplied, can result in hive decline or collapse. The collapse is not immediate; it comes several weeks later and can mystify the beekeeper. The explanation given for this effect is that supplements are not a perfect replacement for pollen; when raising too much brood with artificial diets with no new pollen, nurse bees deplete their body reserves dangerously.

Nonetheless, many people feed only one patty to each hive in the spring, and many of those who plan to use only one patty also choose to feed patties high in pollen content. In my experience, if only one patty is fed, it should be low in pollen, so that it will not stimulate the bees prematurely, and so that it will last. If high-pollen patties are fed, then they should be fed continuously until natural pollen is coming in. That means getting out weekly and replacing any patties that have been consumed.

How much patty each hive consumes is a good indicator of how good the hive is. Queenless or weak hives will eat much less of its patty, and a beekeeper can easily decide which hives in a yard to work on, just by looking at the patties after a week or two.

In my view, inducing unnaturally large amounts of early spring brood rearing is not the best use of protein patties. I prefer to use early patties to nourish the adult bees in hopes that these bees will be in better shape when real fresh pollen comes in and they are needed to rear brood, then continue feeding so even weaker hives have protein available on those days when the weather keeps them confined. Last year we fed three to five patties per hive, ending in June. They were all consumed, and some of the patties had zero pollen content.

Pollen in patties is an attractant, and enhances nutrition, but pollen available for feeding varies in quality. Not only can collected pollen vary due to the plants available when it is collected, but drying and storing will diminish nutritional value. Pollen also declines in value over time to the point where, after three years of storage, even if frozen, it may become worthless. The best pollen for feeding is frozen without drying as soon as it is collected, stored only one winter, and irradiated immediately before being used in patties.

If zero pollen is used, the bees consume the patties at roughly one third the rate (in my experience) of a high-pollen patty. That means low or no-pollen patties will last three times longer -- three weeks instead of one -- and that can be a good thing if a beekeeper is only planning on using one patty, and particularly if he/she is adding that one patty more than a week before fresh pollen is certain to be coming into the hives.

3-5% pollen is our preference. Using 3-5% pollen (calculated on the non sugar and non-water portion of the mix) will roughly double the rate of consumption, in my experience, over patties with no pollen, and that is a good compromise. Remember also, that we keep putting on patties even after the natural pollen flows start because we know that there may be cool or rainy weeks when the bees -- particularly small colonies -- can get out only occasionally, no matter how much pollen is on the trees and flowers.

As I said before, our goal is not to stimulate brood rearing. It is simply to ensure that the protein needs of the adult bees are met until real pollen comes in and that the bees are always in top shape. Our patties encourage slower, but steady, consumption and do not raise the bees? expectations to unreasonable levels.

Although we sometimes neglect to do so recently, we have fed protein patties in fall, and think that fall protein supplementation does reduce winter loss. It certainly does no harm.